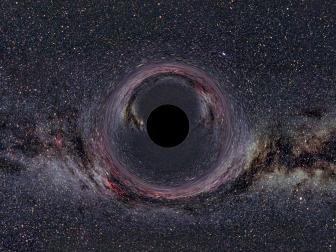

MARK GARLICK/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

The Nobel Prize Fell Into a Black Hole (and That’s a Good Thing)

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics is being awarded to scientists to have dedicated their careers to the study of black holes.

Black holes are kind of a big deal. After that, they are a distinct location in space (as in, you can literally point to them) where all our knowledge of physics completely breaks down. They're so mind-bending that it took scientists nearly a century to convince themselves that they actually, really, truly do exist in our universe. Black holes aren’t just a flight of mathematical fancy, nor the dreams of a feverish theorist. Black holes are living nightmares, monsters haunting the cosmos, and something that the Nobel Prize committee just recognized.

As you might imagine, the Nobel Prize committee is a little slow to recognize achievements in the sciences. After all, what one year (or decade, or century) might appear to be an iron-clad result could be overturned by some new observation or experiment. And cool ideas (and black holes definitely count as “cool ideas”) are just that–-"ideas" until there is enough evidence to convince ourselves that they’re real.

This year, the Nobel Prize award in physics went to three hard-working scientists who spent decades demonstrating that black holes are much more than a cool idea.

The Split

FREDRIK SANDBERG

David Haviland (L), member of the Nobel Committee for Physics, and Goran K Hansson, Secretary General of the Academy of Sciences, sit in front of a screen displaying the winners of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics (L-R) Briton Roger Penrose, Reinhard Genzel of Germany and Andrea Ghez of the US, during a press conference at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, in Stockholm, on October 6, 2020. - Roger Penrose of Britain, Reinhard Genzel of Germany and Andrea Ghez of the US won the Nobel Physics Prize on Tuesday for their research into black holes, the Nobel jury said.

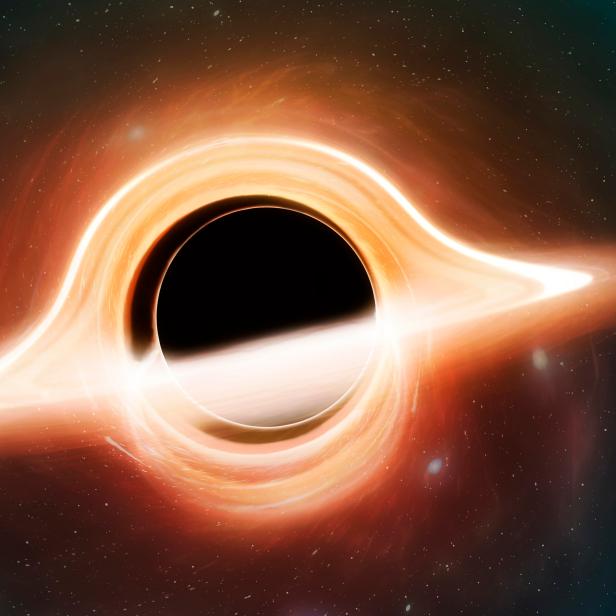

Half the award went to Roger Penrose at the University of Oxford. Decades ago, Penrose worked with his best bud Stephen Hawking to flesh out the concept of black holes and demonstrate that they could actually form in our universe. You see, the very idea of a “black hole” first appeared in the equations of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and nobody really took that bit seriously. For a very long time, scientists just assumed that nature would intervene and that you couldn’t actually manufacture points of infinite density enveloped in walls of you-can’t-ever-come-back-again event horizons.

In other words, scientists just assumed that black holes were too weird to actually exist. And then Penrose came along.

He showed that black holes can happen: that if a massive star ends its life, it can compress down to a small enough volume to form a black hole. He found that black holes aren’t a random freak floating around in Einstein’s math. No, it’s the opposite: black holes are a prediction of Einstein’s math.

Once people started taking black holes seriously, we realized that they were everywhere. We saw them sucking down material from nearby stars. We saw them consuming great feasts of gas and dust at the hearts of galaxies. We saw their gravitational echo when they collided in the dark.

And some people, like the other two winners Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez, didn’t see them at all.

More About Black Holes

There Are at Least 4 Ways a Black Hole Could Kill You

Do we really stand a chance when it comes to black hole?

That’s a (Weirdly) Big Black Hole!

Recently astronomers identified a black hole near a star called LB-1 and they found out that the black hole is 70 times the mass of the sun. This is a mystery because the biggest black holes we can get from the deaths of the most massive stars are around 30 times the mass of the sun, so how did black hole get this big?

Too Big to be a Neutron Star, Too Small to be a Black Hole. What Am I?

Okay, stars die in all sorts of interesting and cosmically expressive ways (except the red dwarf stars, who just sort of…stop).

Instead, they saw something even more frightening. Leading two independent teams, Genzel and Ghez developed sophisticated observing programs to stare at individual stars in the center of our galaxy. Over the course of years, they watched these stars orbit and loop around some massive, hidden source–a giant black hole, weighing over four million times the mass of the sun.

The Breakthrough

FREDRIK SANDBERG

Goran K Hansson (L), Secretary General of the Academy of Sciences, listens as Ulf Danielsson (R), member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, speaks during the announcement of the winners of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics during a news conference at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, in Stockholm, Sweden, on October 6, 2020. - Roger Penrose of Britain, Reinhard Genzel of Germany and Andrea Ghez of the US won the Nobel Physics Prize for their research into black holes, the Nobel jury said.

Their work was a breakthrough, demonstrating that not only do black holes exist, but that they can grow to gargantuan proportions.

The work of Penrose, Genzel, and Ghez (and countless other scientists who didn’t win the Big Prize, because it’s limited to three at a time), brought black holes out of the shadows and into the light. It revealed that we can’t just wish black holes away, and instead have to stare directly into their abyss.