NASA/Hubble

The First Exoplanet Found…Outside the Galaxy!

This new planet has had a pretty rough life.

It’s about the size of Saturn and orbits its parent stars about twice the distance that Saturn does around our sun. But that plural in the previous sentence wasn’t a typo: stars. It’s a member of a binary system, with two stars orbiting each other and the planet (and any of its siblings) orbiting the pair further out.

And one of the stars is dead.

The star died long ago, probably in a cataclysmic supernova explosion that rocked the system. All that’s left is a dense, compact object, either a neutron star or a black hole (exactly what is too hard to determine from this great distance). And as for the other parent? It has swollen, turning into a red giant.

.jpg.rend.hgtvcom.861.431.suffix/1636406577615.jpeg)

NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

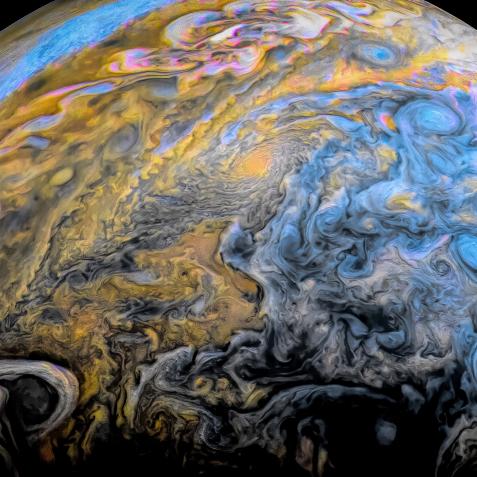

The two stars are locked in a deadly embrace, with the compact remnant siphoning off material from the surviving star. As that material falls, it compresses and heats, releasing intense amounts of X-ray radiation.

But it’s those X-rays that allowed astronomers to observe this system and detect the exoplanet hiding there. Normally, astronomers use a couple of common techniques to find exoplanets, which are planets orbiting other stars. Sometimes a planet crosses in front of the face of its parent star, causing a tiny dip in the brightness, which we can detect if we look carefully enough. Sometimes the planet tugs on its parent star through their gravitational interaction, causing the star to wobble.

But both of these techniques only work to a distance of a few thousand lightyears, well within the limits of our own Milky Way galaxy.

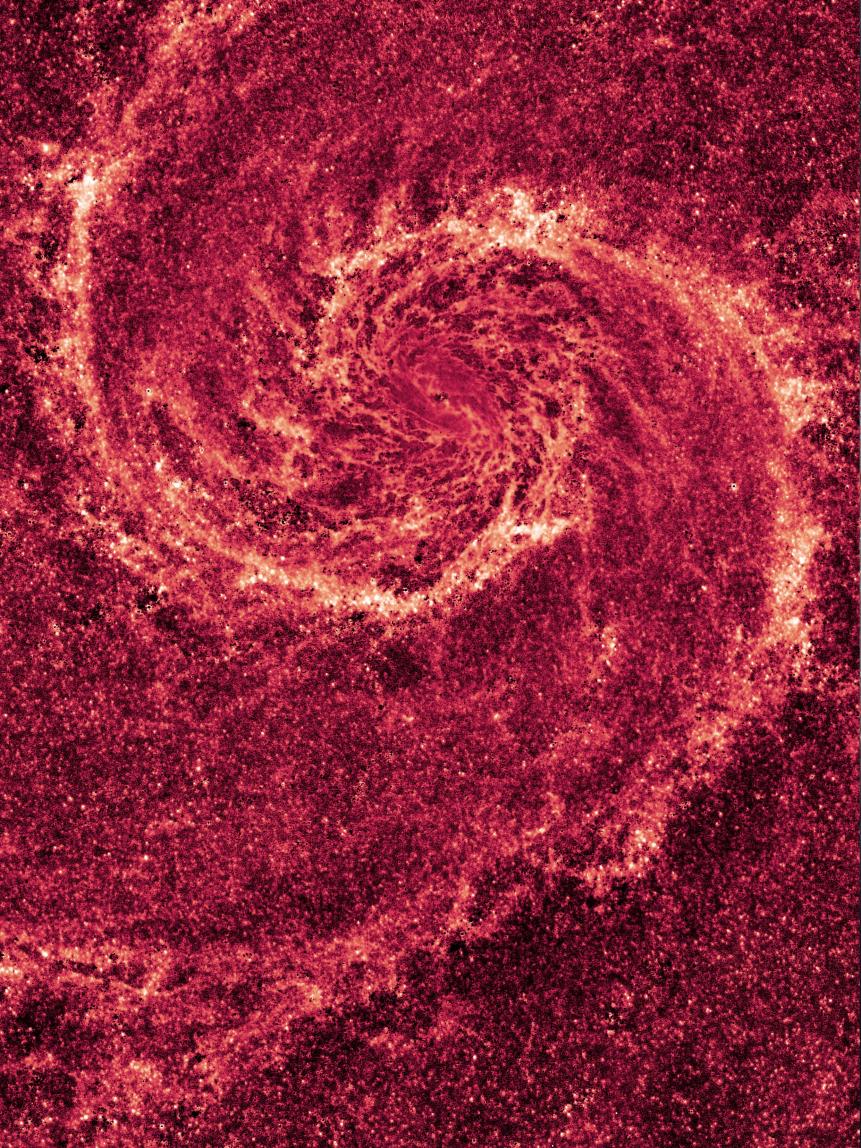

This new exoplanet, orbiting a dead and decaying pair of stars, sits over 28 million lightyears away in the Whirlpool Galaxy.

NASA, ESA, M. Regan and B. Whitmore (STScI), R. Chandar (University of Toledo), S. Beckwith (STScI), and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

The Whirlpool Galaxy, seen in near-infrared light.

The astronomers who made the discovery used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton telescope to scan over 200 systems in three galaxies. For all their work, they found only a single exoplanet.

Their technique relied on pure coincidence: an exoplanet orbiting a system like this, with just the right alignment and just the right time of observation, to catch the exoplanet temporarily covering up the X-ray light emanating from the center. Since the central object (either neutron star or black hole) is so tiny, even a distant exoplanet can cover up a significant portion of it, enabling this kind of detection that would otherwise be impossible.

All told, the astronomers witnessed the X-ray light from the system disappear for about three hours. There are other possible explanations for this dip, like a dust cloud blocking our view, but the astronomers ruled that possibility unlikely. Unfortunately, we’re going to have to wait a long time for a confirmation: with such a wide orbit, the Saturn-sized exoplanet will take another 70 years to circle back around and repeat itself.

Dive Deeper into our Galaxy

Journey Through the Cosmos in an All-New Season of How the Universe Works

The new season premieres on Science Channel and streams on discovery+.