NASA/JPL-Caltech

Got You! Astronomers Find an Especially Sneaky Black Hole

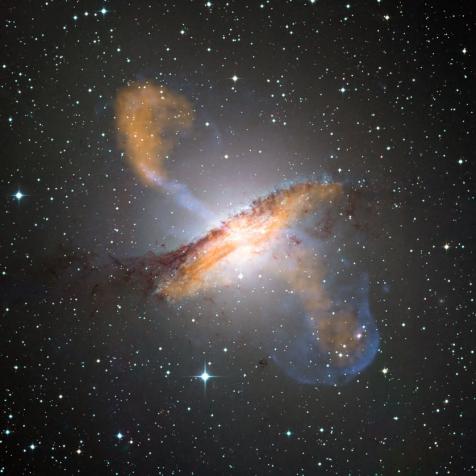

Black holes are tricky creatures. Since ancient times the practice of astronomy has been to point our eyes and instruments at all the glowing things in the skies above us. But black holes are defined by the fact that nothing, not even light, can escape their gravitational clutches. So how you do see something that is completely, totally black?

The usual trick is to wait for a lucky chance (or unlucky, depending on your point of view). Stars aren’t always born alone; in fact, most stars are members of a binary system. If one of those stars in a pair dies and turns into a black hole, and the orbits are aligned just right, then the new black hole can begin sucking down some of the atmospheres from its companion, eating it alive.

As all that gas falls into the black hole, it compresses and heats up to trillions of degrees Fahrenheit, Before finally crashing through the event horizon of the black hole, never to be seen again in our universe, that gas emits enough light to be seen across the galaxy.

So we don’t strictly see black holes themselves, but what they’re doing to their environment.

Until now.

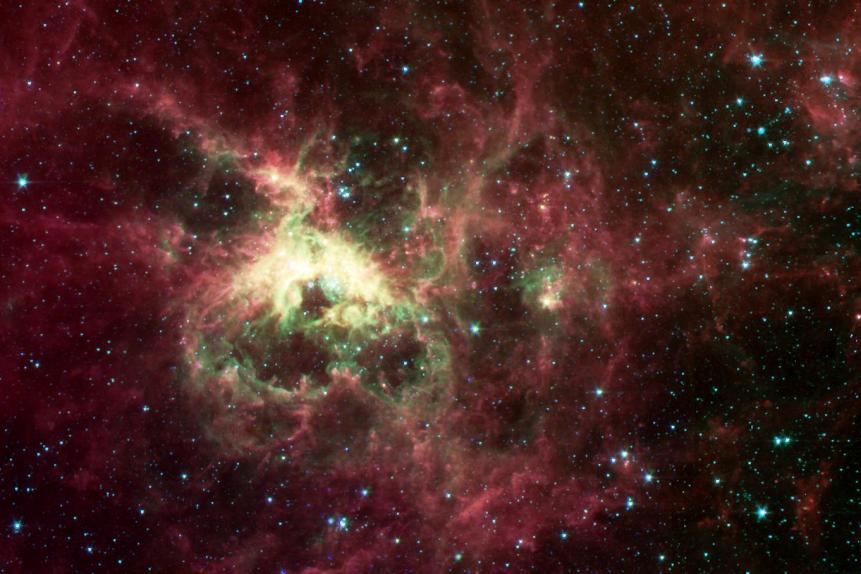

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell University and University of Leiden

A team of astronomers has been busy studying a particular system, called VFTS 243, in the Tarantula Nebula of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy orbiting the Milky Way about 163,000 light-years away from us.

Astronomers have known about this system for a long time and had long suspected that it consisted of a giant blue-white star about 25 times more massive than the sun and a much smaller companion. They could determine this based on the light coming from the star – the astronomers could tell that it was in orbit around some companion. But what was that companion? A dangerously close black hole, or just some dim, small, boring star?

The astronomers were able to determine that all the light coming from the system is emanating from just a single blue-white star. There is no light coming from the smaller companion, at all.

Hmmm, small, dense object not emitting any light? Sounds like a black hole. Based on the orbit the black hole has a mass a few times that of the Sun but is only 33 miles across. It’s small enough and far enough away from its companion that it’s not able to suck down any of its gas, so it doesn’t light up for us.

We honestly don’t know how many black holes are truly out there. We only have rough estimates based on our understanding of the life cycles of stars and the examples of lit-up black holes that we’re able to find. This new result is huge, as it opens up the possibility of finding black holes in a brand-new way.

Who knows what other monsters are waiting for us, out there in the dark?

Paul M. Sutter

Dive Deeper into the Universe

Journey Through the Cosmos in an All-New Season of How the Universe Works

The new season premieres March 24 on Science Channel and streams on discovery+.