NASA/Bill Ingalls

Why Mercury Matters

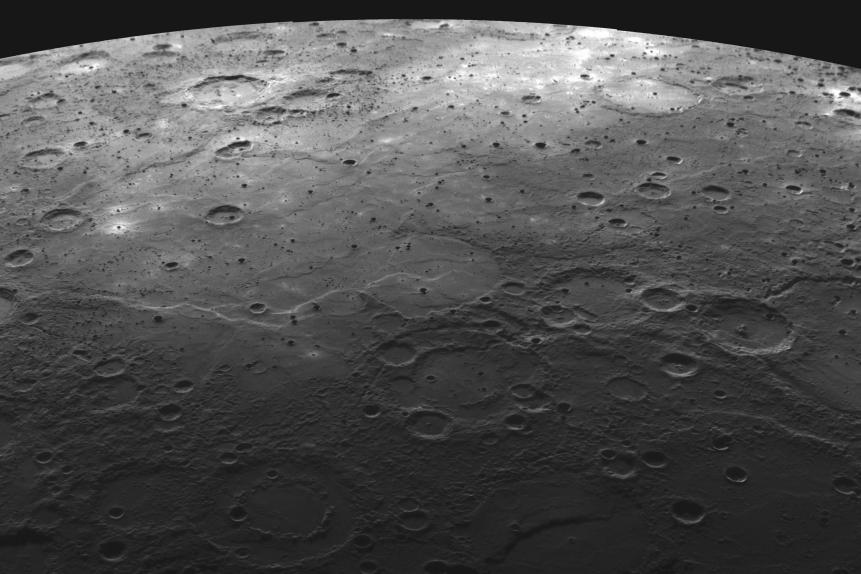

At first, the planet Mercury isn't much to look at. It has a surface only a mother could love, as desolate and empty as the Moon and pock-marked with crater after crater. But this planet has a secret, which has folks wanting to know more.

Mercury is the smallest of the four inner rocky worlds of the solar system, not even half the width of the Earth. And it's mostly just a big ball of rock. So why did NASA send the Mariner 10 probe to the planet in 1974? And the MESSENGER spacecraft a decade ago? And why did the Japanese and European space agencies join forces to develop BepiColumbo, a two-craft space probe that will reach the planet in 2025?

Because Mercury has a secret.

Yes, by all accounts Mercury is a dead world. You can tell that by its craters. Worlds capable of active resurfacing, like from plate tectonics or weathering, will eventually erase their scars. That’s why you don’t see a lot of craters on the surface of the Earth. But you do see them on Mercury – it hasn’t been molten in a long, long time.

The temperatures on Mercury are extreme. Because it’s the closest planet to the Sun, it gets blasted on its daylight side, with temperatures reaching up to 800 degrees Fahrenheit. But on the night side, away from the Sun’s persistent glare, the temperatures can plummet down to -280 degrees.

NASA, JHU APL, CIW

Why are many large craters on Mercury relatively smooth inside? Images from the MESSENGER spacecraft that flew by Mercury in October 2008 show previously uncharted regions of the planet that have large craters with an internal smoothness similar to Earth's own moon, and are thought to have been flooded by lava floes that are old but not as old as the surrounding more highly cratered surface.

In fact, there may even be water ice on the surface. Some craters are deep enough that they remain in permanent shadow, even in the daytime, and without much atmosphere to speak of, they stay cool enough all day long.

But the real big mystery about Mercury is its magnetic field. It’s incredibly weak, barely 1% the strength of the Earth’s. But by all accounts, even that is an astounding feat, because Mercury isn’t supposed to have a magnetic field at all.

Planets generate magnetic fields in their cores. Those cores typically contain the heaviest elements of a planet, like iron and nickel. If the cores are hot enough to be molten, then those metals will melt. As the planet spins, that metal, molten core swishes around, which is exactly the conditions you need to power up a magnetic field.

But Mercury doesn’t have much of a molten core. It’s so small that its inner core has completely cooled off by now and is now rock solid. It still maintains a little bit of a liquid outer, core, however, but it’s not exactly big.

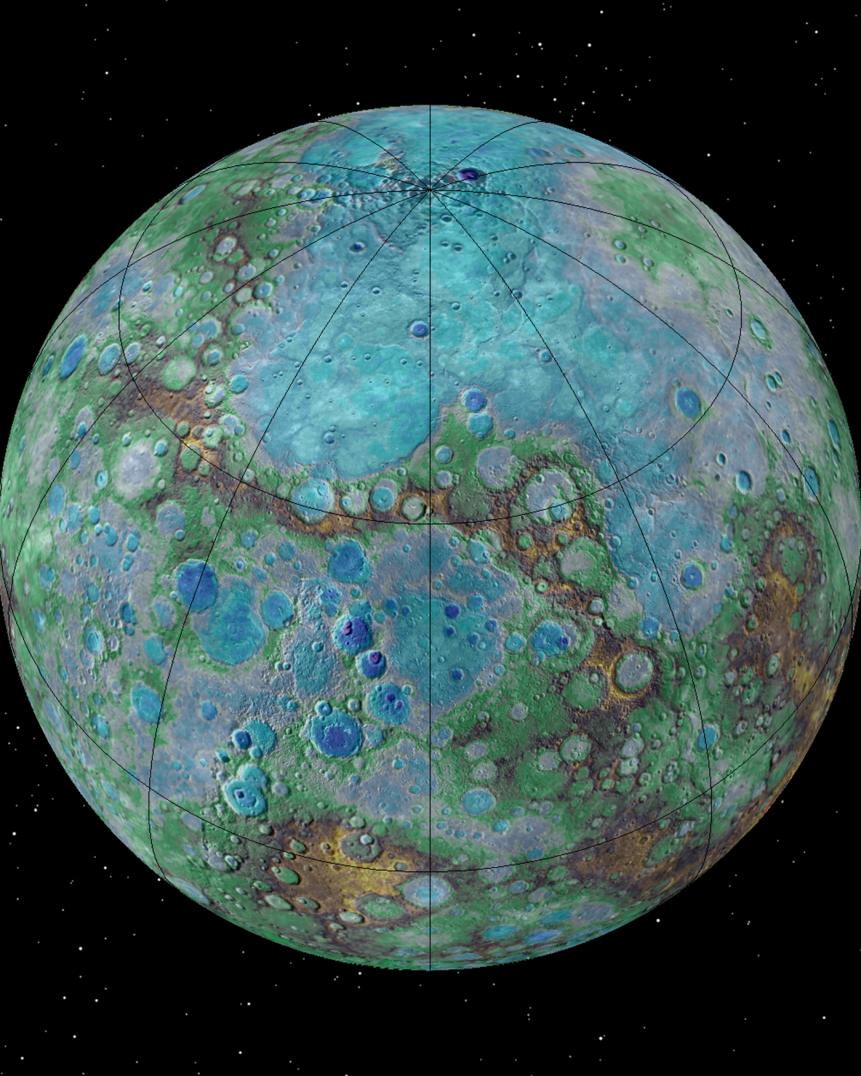

NASA/JHUAPL/Carnegie Institution of Washington/USGS/Arizona State University

It’s small, it’s hot, and it’s shrinking. New NASA-funded research suggests that Mercury is contracting even today, joining Earth as a tectonically active planet. Images obtained by NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft reveal previously undetected small fault scarps— cliff-like landforms that resemble stair steps. These scarps are small enough that scientists believe they must be geologically young, which means Mercury is still contracting and that Earth is not the only tectonically active planet in our solar system, as previously thought.

And Mercury barely rotates. A single “day” on Mercury lasts over 58 Earth days.

Before the Mariner 10 mission, astronomers and planetary geologists just assumed that Mercury could never get its act together to form a magnetic field. But there it was, staring them in the face.

Hence MESSENGER and BepiColumbo, both designed to try to understand the origins of this mysterious magnetic field.

Dive Deeper into the Universe

Journey Through the Cosmos in an All-New Season of How the Universe Works

The new season premieres on Science Channel and streams on discovery+.