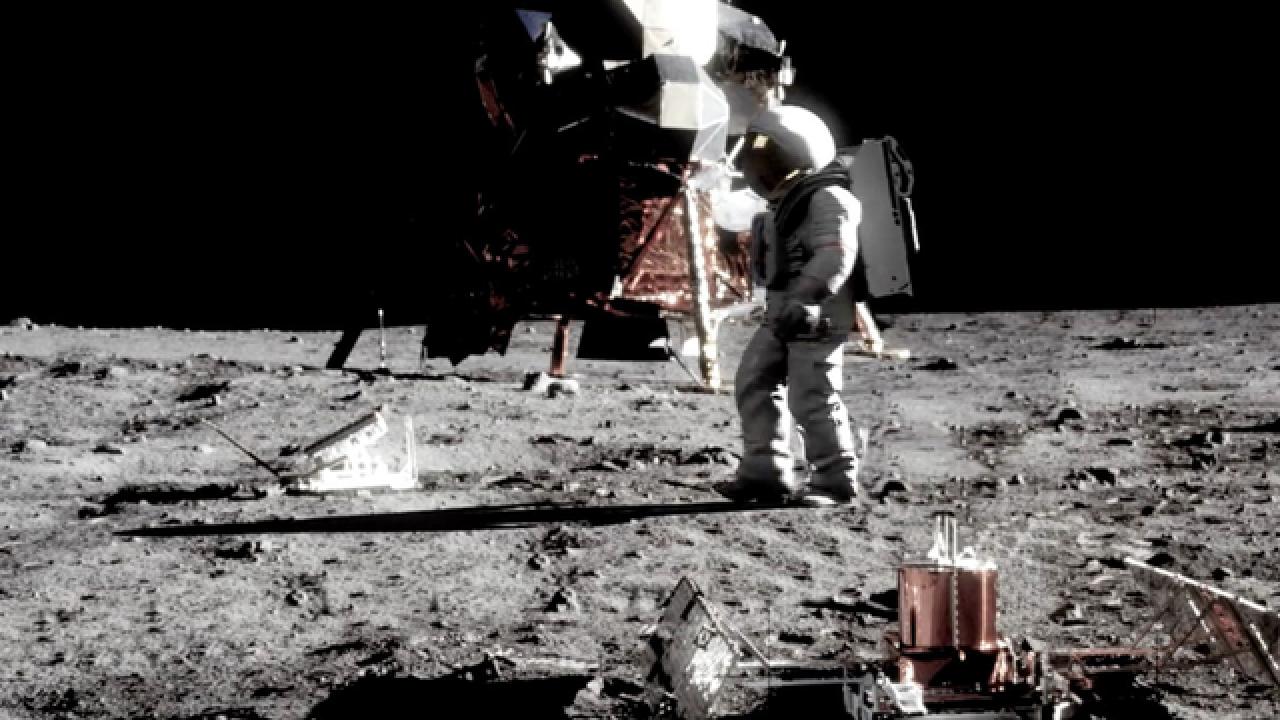

GettyImages/NurPhoto

Let’s Look for Water on the Moon

NASA is headed to the moon, but this time it's in search of water. Astrophysicist Paul M Sutter shares what this means and why it's important.

NASA certainly has a knack for acronyms. In this case, the rather stuffy-sounding Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover sounds way better as the VIPER mission. And the VIPER mission will rove around on the crater-pocked Lunar surface, finding any water it can, take a sip, and let us know if it’s good enough for human consumption.

This mission is a part of a larger NASA initiative to send people to the moon (again). Named Artemis, after the Greed goddess who was the twin sister of Apollo, the god of the moon, NASA’s goal is to get the first crew awkwardly skipping on the surface in the low Lunar gravity by 2024. But before we start shuttling astronauts over there, we first need to decide on a good landing site, a site good enough that it can hopefully serve as a home base for future exploration and – in our wildest dreams – habitation.

As you may have noticed the last time you got thirsty, humans really like water, and so any long-term presence on the Moon will be aided by water already there just laying around, rather than having to cart it over from the Earth, which makes missions that much more expensive.

But as we all know, the moon is a frigid, airless lump of unremarkably grey rock. Can there really be water there?

The answer is, surprisingly, yes.

If the Moon formed with any water billions of years ago, it also lost it billions of years ago: without an atmosphere to keep a lid on things, liquid water doesn’t like to hang around on the surface of a world. But over the eons water-rich comets have occasionally crashed into our satellite, as evidenced by all the massive impact craters dotting its landscape.

Most of that water was also lost, but some craters are near the poles, where due to the tilt of the Moon itself, some pockets are kept in permanent shadow. There, the water can turn into ice, and without the incessant glare of the sun to melt it away, it can stay.

That is, until we dig it up and drink it.

GettyImages/Finnbarr Webster

The VIPER mission will target one of these craters, perhaps the one where NASA previously slammed a scientific torpedo into the surface, which reported back the distinct presence of water. Once there, VIPER will rove around, occasionally sinking in a meter-long drill, hunting for the good stuff.

We don’t think that lunar ice comes in the form of big chunks or sheets like we would find on the Earth, but rather as thin coatings around dust grains. The VIPER mission will answer a critical question: is there enough water ice in the Lunar soil that we could use it to support crewed missions there? The answer to that question will help inform future mission design and planning, especially those in the upcoming Artemis program.

So raise a glass to VIPER, and hope that when it travels to the Moon in 2022, it finds something for us to drink.