Paul Fleet

The Kuiper Belt: When Solar Systems Dance

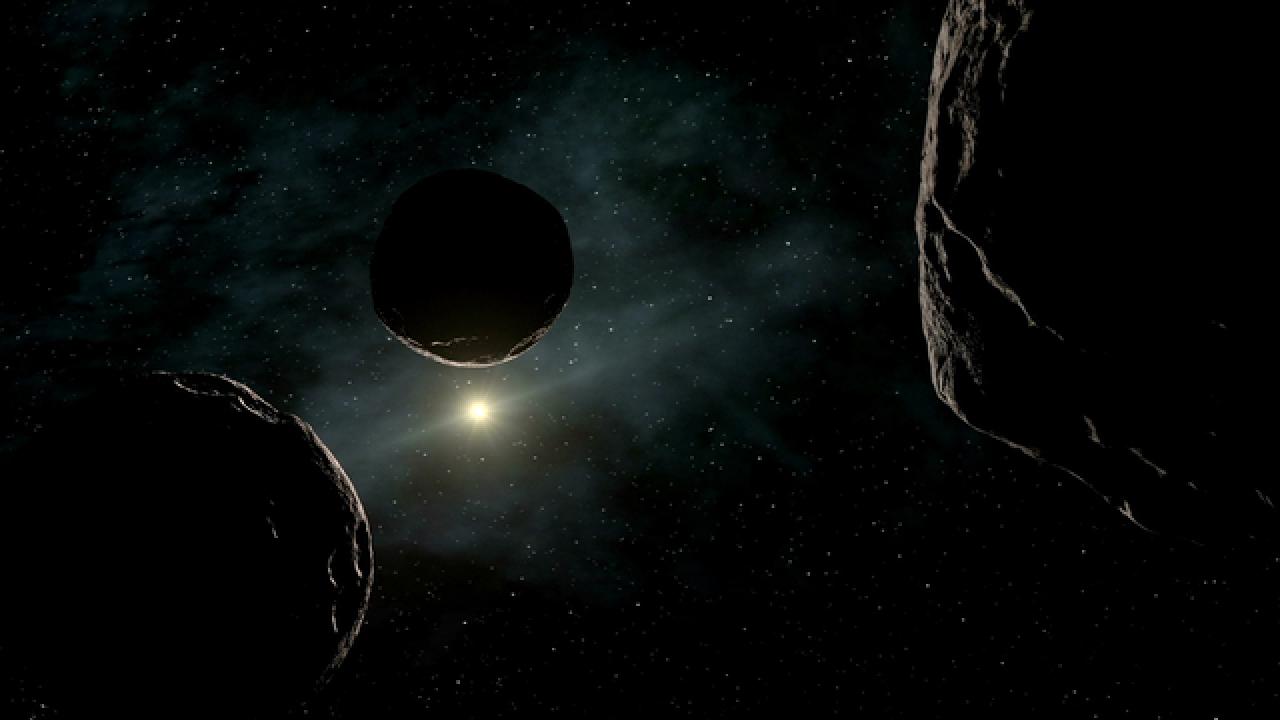

Pluto isn't alone after all. Besides being the home of Pluto, the Kuiper belt hosts dwarf planets, and smaller bits of rock and ice.

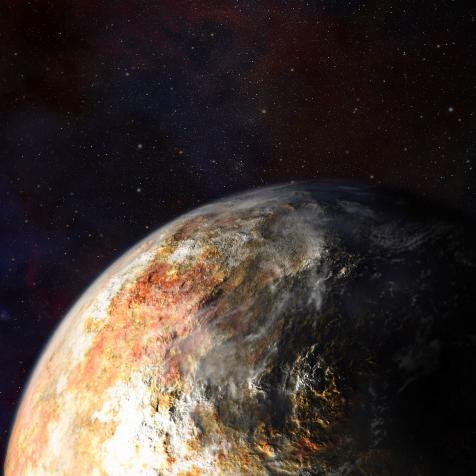

I’m sure you know about Pluto, that renegade rock that managed to convince us for a few decades that it was a member of the planet family in the solar system, until some astronomers defined the word “planet” in a perfectly precise way so as to exclude it from the Big List.

But did you know that Pluto isn’t alone?

And by “not alone,” I mean it has roughly 100,000 friends, all orbiting the sun in the cold, distant wastelands of the solar system.

That cold, distant wasteland goes by a name: the Kuiper belt, named after Dutch astronomer Gerard Kuiper who was one of several in the mid-twentieth century to hypothesize that the region of our solar system past Neptune is anything but empty. However, Gerard thought that this region was anything but empty in the past, but by modern times (i.e., within the past billion years) had been cleared out. For some strange reason known only to astronomers, his name stuck.

The Kuiper belt starts just past the orbit of Neptune, or 30 AU to about 50 AU, with the precise boundary depending on which astronomer you ask. For those of you not up-to-date on random astronomy jargon, an “AU” is short for “astronomical unit”, or the distance between the Earth and sun – so “30 AU” means 30 times farther away from the sun than the Earth is.

Besides being the home of Pluto, the Kuiper belt also hosts two other dwarf planets, Haumea and Makemake, and thousands of other smaller bits of rock and ice. However, we know that there are a lot more bits out there, but they’re hard to see because they are a) small and b) very far away. So right now, we suspect there are about 100,000 “Kuiper belt objects” or “KBOs” if you want to be snappy about it. And if you want to get downright silly about it, the main population of KBOs are called “QB1-o’s” or, and I swear I’m not making this up, “cubewanos”.

In short, the Kuiper belt is like the asteroid belt, but bigger and colder.

Mark Garlic - SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

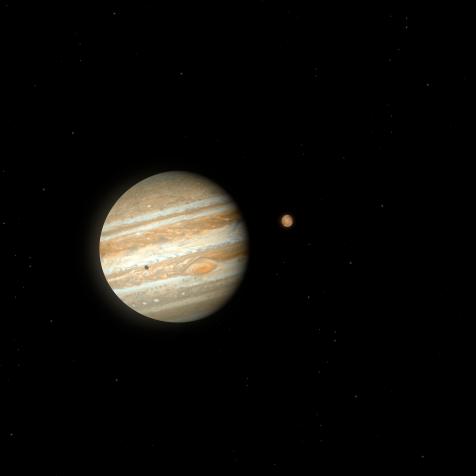

Astronomers suspect, based on a lot of math and some computer simulations, that the Kuiper belt formed pretty early on, just after the major planets formed. Back then, the biggest giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) were much closer together, surrounded by a retinue of smaller wannabe’s, the planetesimals.

After their formation, Jupiter and Saturn migrated closer to the sun, which through a little bit of gravitational doe-see-doe sent Uranus and Neptune to orbits farther away. As you might imagine, when giant planets start moving around, havoc ensues.

As Uranus and Neptune drifted away from the sun’s embrace, their gravitational might sent some planetesimals shooting out of the solar system altogether, doomed to wander the interstellar vastness alone. But some hung on, being shepherded by those giant planets on their outward migration. In the outermost reaches of the solar system, they found refuge in the form of stable orbits, allowing them to hang on – barely – to the solar system. Today, they orbit in quiet solitude, remembering forever the more heady, more active early days.

#TeamPluto premieres Tuesday, February 18th at 11pm ET/PT on Discovery and Discovery Go.