SEBASTIAN KAULITZKI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Indoor Pollutants are Microscopic and Potentially Dangerous

As most people now spend around 90% of their time indoors, digging into dust holds up a microscopic mirror to our everyday lives.

Household dust may be one of the more mundane materials available to scientific study, but research shows that it contains a fascinating mix of elements from our modern lifestyles.

Home: Safe or Not So Much?

allanswart

In periods like the coronavirus pandemic lockdown, our exposure to household dust and its contents take on increased importance. So projects such as 360 Dust Analysis are undertaking global research to find out what harmful chemicals are in our living environments.

Allied project Map My Environment offers a living data visualization on its website for dust and other sources of pollution in cities around the world. Both projects use citizen scientists to gather samples and then analyze the dust data to help scientists and communities tackle pollution together.

The origin and chemistry of indoor dust is vastly complex and so are its effects, says Jonathan Thompson, a post-doctoral researcher for Map My Environment's 'Home Biome' team.

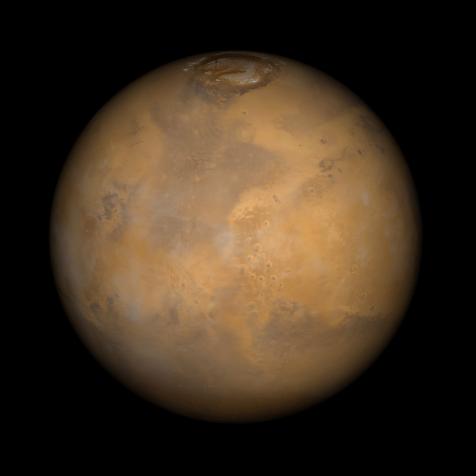

Too Small to See

Callista Images

Dust and other particles in our homes come from outdoor air, roads, or building sites, plus debris from our kitchens and bathrooms and air cooling and heating systems. Typically, dust contains human skin cells, hairs, man-made and natural fibers from clothing or furniture, bacteria, fungi, microplastics, soil and minerals, metals, plant pollen, and dust mites.

Our homes have their own biological communities, or biomes, says Thompson. More than 2,000 different types of fungi have been discovered in dust, dependent on the outdoor climate, indoor ventilation, and building materials used. Multiple bacteria also thrive according to the people, different genders, personal hygiene, and activities, plus any pets living in our houses.

Bacteria are part of the natural microbiota associated with humans and pets. People contribute microbes from their skin (including Staphylococcus aureus and Corynebacterium) and the human gut. But the biggest concern comes from occasional samples such as anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) or Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) found in residential dust, specifically from vacuum cleaners, showing that they can harbor harmful bacteria, says Thompson.

MRSA has proven to be a persistent problem in healthcare settings where it can cause infections and pneumonia. Anti-microbial resistance in bacteria, particularly to antibiotics that have saved millions of lives since their discovery, is one of the greatest challenges facing medicine today.

Resistant genes have been found in multiple studies of indoor dust and even aboard the International Space Station. Those genes can transfer between different bacteria, so it is possible that our homes and offices could become reservoirs of antibiotic resistance.

Selective environmental pressures could also increase the risk of that happening, such as the presence of trace metals like lead, copper or zinc that play a role in antimicrobial resistance, says Thompson. Still more study is needed, he says, noting that “ the predominant risks are associated with exposure to allergens found in house dust and can be mitigated by regular cleaning.”