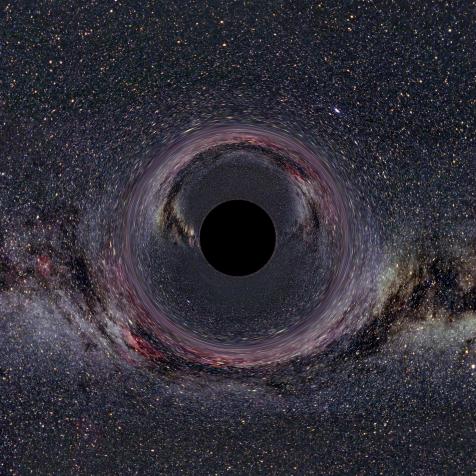

Getty Images/WLADIMIR BULGAR/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY,

5 LGBT Scientists Who Changed the World

Without their scientific accomplishments, the sciences would be very different today.

You can't help but see the world through your own experience. Scientists are no different. While the scientific method helps to cut down on how much influence any particular scientist has on an experiment's results, humans are still deciding what to study and how to interpret those results. That's why diversity is important — when you have different people from different backgrounds making different decisions about how to investigate the world around them, you get a more complete picture of that world. June is LGBT Pride Month in the United States, so in honor of the unsung groups who enrich the realm of scientific discovery, here are five LGBT scientists from history.

Wikimedia Commons

Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626)

As many of his stature were at the time, Sir Francis Bacon was a jack of all trades — a lawyer, a statesman, and a philosopher. It was that last one that led to his claim to fame: He's remembered as the father of the scientific method. While science textbooks celebrate these accomplishments, they usually leave out the fact that he was most likely gay. Several dozen of the 75 attendants in his household were "gentleman waiters," many of whom Bacon gave lavish gifts and important appointments — and letters between Bacon's mother and brother suggest that Bacon considered many of them to be much more than servants. One particularly handsome young man, Sir Tobie Matthew, became Bacon's closest friend and confidant, and the inspiration for one of Bacon's most famous essays: "Of Friendship." His social life aside, we might have a much bleaker understanding of the universe today without his brilliance.

Getty Images

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910)

While Florence Nightingale is most known as a nursing pioneer, she was also a trailblazing statistician whose prowess for numbers literally saved lives. She even made important contributions to data visualization — if you've ever seen a Coxcomb diagram, you've seen her handiwork. Nightingale is known to have had two passionate relationships with women during her life. One was with her aunt Mai Smith, who nursed her back to health during a serious illness and "became her protector, interpreter, and consoler." The other was an unrequited infatuation with a cousin named Marianne Nicholson, of whom Nightingale wrote, "I have never loved but one person with passion in my life, and that was her."

Wikimedia Commons

Alan Hart (1890–1962)

You won't find Alan Hart in many encyclopedias or science textbooks, but he's of particular importance on this list for both who he was and what he achieved. A Yale-trained public health expert and researcher, he became a prominent figure in the fight against tuberculosis, which at that time was a leading cause of death in the United States and much of Europe. He was also one of the first female-to-male transgender people in the United States to undergo a hysterectomy and live the remainder of his life as a man. After graduating from medical school, he sought psychiatric help from one of his professors, J. Allen Gilbert, and eventually asked him to perform the operation. It was a gamechanger for Hart, giving him, as Gilbert wrote, "a new hold on life and ambitions worthy of [his] high degree of intellectuality." Hart married twice, wrote numerous novels, and served as the director of hospitalization and rehabilitation at the Connecticut State Tuberculosis Commission until his death.

Wikimedia Commons

Alan Turing (1912–1954)

Alan Turing's story might be the best known in the history of LGBT scientists, and the saddest. Even if you don't know his story, you know his work — you're using it right now. Alan Turing is the namesake behind the Turing machine, which is the basis for all computers. He was also responsible for breaking the Nazi Enigma code during World War II, a feat highlighted in the 2014 film The Imitation Game. While the societies of some of the other scientists on this list may have accepted their unorthodox lifestyles, or at least looked the other way, homosexuality was a crime in mid-century England. Despite this, Turing was open with his friends at King's College in Cambridge and pursued relationships with men beyond that circle of safety. He was arrested for "indecency" in 1952, pled guilty, and was punished via hormone injections that left him impotent. Two years later, he's believed to have killed himself by eating a cyanide-laced apple. It wasn't until 2013 that the British government granted a posthumous pardon to this computing pioneer and war hero.

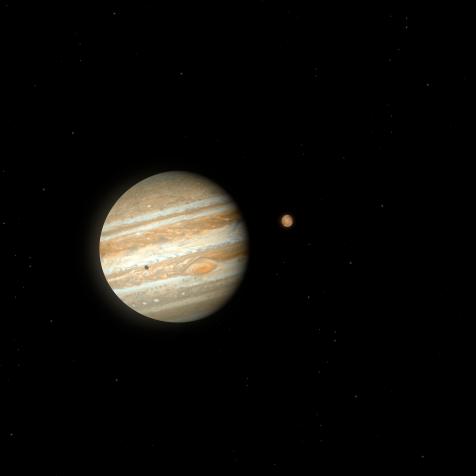

NASA

Sally Ride (1951–2012)

On June 18, 1983, Sally Ride became the first American woman in space, flying aboard the space shuttle Challenger. She later became the director of the California Space Institute at the University of California, San Diego, and started her own nonprofit company, Sally Ride Science, in 2001 to inspire children to pursue their interests in science and math. She founded that company with the help of two friends and her partner, Tam O'Shaughnessy. "Most people did not know that Sally had a wonderfully loving relationship with Tam O'Shaughnessy for 27 years," Ride's sister Bear wrote after her death from pancreatic cancer in 2012. "Sally never hid her relationship with Tam. They were partners, business partners in Sally Ride Science, they wrote books together, and Sally's very close friends, of course, knew of their love for each other. We consider Tam a member of our family." Today, O'Shaughnessy honors her partner's legacy as the executive director of Sally Ride Science.

This article first appeared on Curiosity.com.