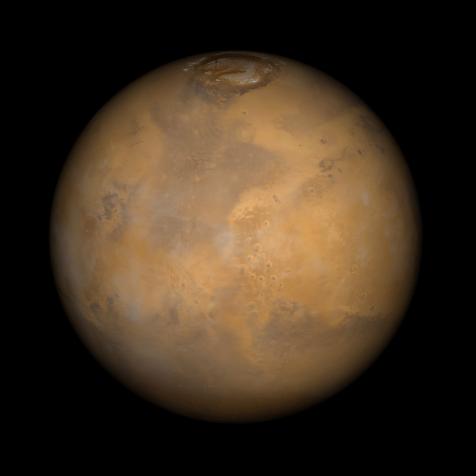

Photo by Bill Ingalls/NASA via Getty Images

WASHINGTON, DC - NOVEMBER 11: In this handout provided by NASA, the planet Mercury is seen in silhouette, center, as it transits across the face of the Sun, behind the Washington Monument, November 11, 2019 in Washington, DC. Mercurys last transit was in 2016 and the next wont happen again until 2032. (Photo by Bill Ingalls/NASA via Getty Images)

Today Mercury Crossed the Face of the Sun

Today, from 7:35 am to 1:04 pm ET, Mercury lined up with the sun, which is called a transit. But what does this mean? Why is it rare? Read on.

Okay, some basic solar system facts. First, the sun is the giant, blazing hot thing in the middle of it all. We live on the Earth, orbiting a respectable 93 million miles away from it (in other words, “very far away”). The planet Mercury, however, tolerates the heat much better than we do, and orbits only 36 million miles from the sun. That’s still ridiculously far away from our parent star, but it’s close enough that the daytime temperatures on that world reach a sweltering 800 degrees Fahrenheit.

Another fact: every once in a rare while, things in space tend to line up in front of each other. This part is not at all important, even though for a long time we assumed that these coincidences meant something significant. For example, when the moon crosses paths with the sun, causing a solar eclipse, people used to think that the world was ending, or worry that a war was about to start, or realize that they had forgotten to pick up their dry cleaning.

Today, from 7:35 am to 1:04 pm Eastern time, Mercury lined up with the sun, something called a transit. This is a pretty rare thing indeed; because the orbit of Mercury is tilted with respect to our own, we only get this treat every few years. And if you live in the United States, we’re in for a very unlucky streak, as the next visible one won’t be until 2049.

Bill Ingalls/NASA

To put it mildly, it’s hard to watch a transit of Mercury yourself.

For one, the sun pumps out dangerously copious amounts of infrared and UV radiation, and since your retinas don’t have pain nerve endings, you can stare at the sun all day long thinking you’re doing just fine, but really your eyeballs are getting cooked to the point of blindness. So, don’t do it. At least not without specialized telescopes with advanced filters (that work by blocking 99.9999% of the incoming light).

Second, Mercury is tiny, only 3,000 miles across. That’s just a tad further than the flight from New York to LA. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the sun is huge – over a million Earths could fit comfortably inside its volume.

Giant star, small planet. Putting together all the numbers and doing a little trigonometry, Mercury in transit appears as a tiny black dot only 1/194th the size of the sun. So to watch a transit, you need a decent telescope.

Besides being a challenging delight for amateur stargazers, transits of Mercury have been used through the ages (and continue to be used through the present age) for all sorts of Serious Scientific Inquiry, mostly by comparing the details of one transit against the hundreds that we’ve recorded in the past. For example, if the sun is transforming itself by changing its size, the length of the transit will give us a clue. On our side, if the Earth is changing its rotation speed (though, say, tidal interactions with the Moon), then that also affects the timing of the transits. We’re also using Mercury transits to calibrate our hunts for planets around other stars, as we use this exact same transiting situation to watch for the subtle dimming in brightness from an alien star.

In summary: transits of Mercury don’t affect you at all, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t important.