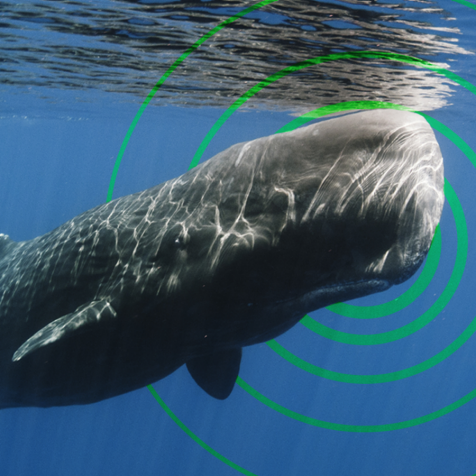

GettyImages/Safique Hazarika Photography

Ships of the Desert out in the Indian Ocean

Learn how mangroves and camels are deeply connected.

Noor Mohammed, who comes from a long line of camel herders, remembers two things his grandfather told him when he was a child. One, their camels can predict the rain. If they lie in in the morning, then it’s only a matter of days or maybe even hours before it will lash down. Second, if it’s going to be a hot day, the camels will enter the water so you better find yourself a nice shady tree to lie under and watch over them.

It’s a weird picture: camels - the “ships of the desert” - bobbing around in gushing water. But the camels in question are a breed called Kharai, found in the western Indian state of Gujarat. They don’t just get into the water when it’s hot, they swim in the open ocean with their herders in tow. They are the only camels in the world that do this and can go up to 3 km offshore. Their name, ‘Kharai’, translates to ‘salty’ after the ecosystem they have adapted to – brackish water and coastal mangroves - and their main food source are the avecinia mangroves that comprise around 90% of the plants in the region.

“If they don’t eat mangroves, they become really sad and weak and eventually die,” says Noor Mohammed. “So if a camel is unwell, or if we’ve just kept one or two at home because they are either young or especially affectionate, we bring back mangroves from the coast for them to chomp on at home.”

“Just as Kharai camels cannot survive without mangroves, the mangroves can’t survive without the camels either. It’s like the neem tree (Azadirachta indica) in my garden that I prune,” says Mohammed. “Camels feed on small mangrove sapling and this helps them grow more abundantly.” A crucial part of the ecosystem here, mangrove forests are the first defense for communities that live close to the coast from storms, cyclones, and tsunamis. They also play a key role in sequestering carbon. Mahendar Bhanani of Sahjeevan Trust who works with the camels, herders, and mangroves systems in the region, says that the camels here are sort of the ‘ecosystem engineers’ of the mangroves - supporting the plants and a host of other species that depend on them, just by maintaining the growth of the mangroves.

GettyImages/Jigar Kapdi

“Camels cannot exist without mangroves and neither can they exist without us maldhari (nomadic tribes),” says Mohammed “And maldhari are nothing without our camels.” Mohammed has stayed for up to 18 days at a time on mangrove islands as his herd feeds. “We drink nothing but milk when we are with them - and it has magical properties,” he insists.

The unt (camel) maldhari as they are called have bred camels for as long as any of them can remember. But things are changing fast. Where there were once thriving mangroves, the fast-developing state of Gujarat has now pushed for salt farms to take over as cement factories and windmill farms also dot the horizon. Mohammed has lost several camels in the last few years. Some cannot make the long walk or swim to the distant mangrove islands, and others have succumbed to cement dust that coats the mangrove leaves and ends up filling their digestive tracts. His brother Ismail says, “It is almost like the camels can sense the destruction the salt farms and industries are causing. They begin to tremor with fear as they approach them.”

The nomadic tribes have had to slowly change their migratory lifestyle that was based on where their camels went in different seasons. They swam with them through creeks and walked across the desert. “We are now completely surrounded by industry, our traditional routes cut off, and have had to settle down in a village,” says Mohammed. “I can’t live without my camels and I tell my children that this is our work - but I also need to push them to find something else that will help them earn money because otherwise you are nothing today.”

In the last few years, more and more maldhari have found themselves boxed in, and their camels have had to walk further and further out for their favorite salty meal. Tribal leaders, along with the help of trusts like Sahjeevan, have formed the Camel Breeders Association to push back and fight to maintain their way of life. They managed to get a stay on the construction of a few large salt farms in their region of Gujarat. They’ve also worked to get the Kharai camels recognized as registered as a breed as recently as 2015 and are working on selling camel milk in local markets as a healthier alternative to cow’s milk. “I would never let my camels go,” says Mohammed, “and with the momentum that the Association has been able to gether, monetizing the milk to keep our livelihood sustainable and pushing back the big industries has given us a new lease of life to keep doing what our ancestors did in a new age.”