Stephen Frink

Great Mysteries of the Deep: How Sharks Find Their Way Home

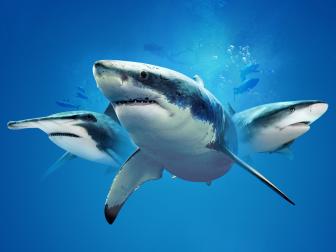

How are sharks able to travel thousands of miles across the ocean and return to the same exact locations year after year? Last month, researchers found the answer to one of the greatest mysteries in the animal kingdom.

In 2005, scientists tracked a great white shark’s trans-oceanic swim from South Africa to Australia and back again in a nearly perfect straight line. This epic 6,900-mile-swim increased speculation that sharks use their electromagnetic sensitivity to navigate open waters.

Finding Their Way “Home”

Rodrigo Friscione

A school of sharks migrates through Mexico.

Sharks’ noses have special receptors which help them sense changes in voltage. Prior research has shown sharks use these electroreceptors to detect nerve impulses in their prey, making them apex predators. Could these receptors be used to guide sharks on their lengthy voyages across the open ocean?

Researchers at Florida State University, led by Bryan Keller, decided to test this theory on a smaller member of the hammerhead shark family — bonnetheads. Bonnetheads are known for returning to the same estuaries each year, proving that sharks know where “home” is and are able to navigate long distances to make it back.

Are bonnetheads able to make their way home each year by relying on a magnetic map? To find out, Keller’s team exposed wild-caught bonnetheads to a series of magnetic displacement experiments.

Shark Week Is Our Favorite Thing About Summer

Get ready for the best summer yet. This year, SHARK WEEK starts on July 11 with more jawsome shows than ever before on Discovery and discovery+.

The team placed the juvenile bonnetheads in a pool one by one and used copper wiring under the pool to expose the sharks to a series of three electromagnetic currents. These electric currents mimicked Earth’s natural magnetic field at the spot where the sharks were collected, a spot 600 kilometers north, and a spot 600 kilometers south.

When the sharks were exposed to the electromagnetic current that mimicked “home” they swam around randomly. But when the sharks were exposed to electromagnetic currents from 600 kilometers south of their home, they immediately swam north toward home. This finding suggests sharks use electromagnetic fields for long-distance migration.

While this study used a smaller species of shark, Keller says other sharks, like the great white, which travel even longer distances than bonnetheads, would find an even greater use from this magnetic “sixth sense.”

Nature’s GPS

Jay Fleming

Bonnetheads are a small member of the hammerhead genus, making them an easier subject for the experiment.

"How cool is it that a shark can swim 20,000 kilometers round trip in a three-dimensional ocean and get back to the same site?" asks Bryan Keller.

Scientists have long described the earth’s magnetic field as “nature’s GPS.” This study adds sharks to the growing list of animals — including sea turtles, salmon, birds, and lobster — who use a magnetic sense for navigation.

The growing pool of knowledge around sharks’ navigation may one day help us understand if humans could be unintentionally blocking or confusing sharks’ navigation with submarines and high-voltage deep sea cables. Scientists look forward to doing more research on the subject to better understand deep sea infrastructure’s impact on migrating sharks.