Getty Images

Almost Every Mammal Gets About 1 Billion Heartbeats

You only have a limited number of heartbeats in your life.

It's strange to think that you have a limited number of heartbeats in your life, but at least you can take some solace in the fact that no one can ever say how many exactly you'll get, right? Wrong. Science knows. And it's about the same for almost every mammal.

Same Song, Different Tempos

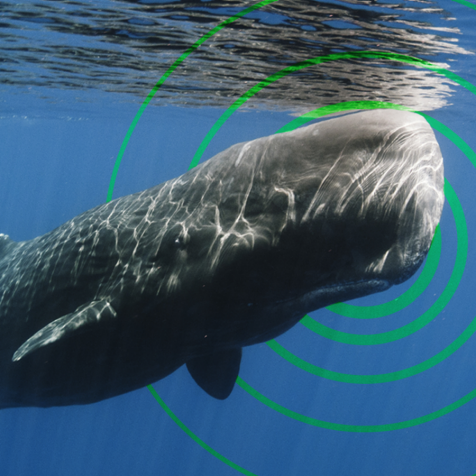

Rabbits live about three years. Elephants can get up into their 80s. But both of them get about one billion heartbeats in their lifetime. It's just that elephant hearts beat a lot slower. As it turns out, that number stays (roughly) the same across other species of mammals. You might also have noticed that elephants are slightly larger than rabbits are, and there seems to be a similar correlation between size and lifespan. Is this indicative of a deeper truth of biology? Or even of the universe? It just might be — but more on that in a moment.

Before we get into the really head-trippy stuff, let's talk about the exceptions to the rule. Thanks to modern medicine, food preservation technology, and our habit of purifying our water sources, human beings have been able to extend our hearts' lives far past the one billion limit. We get a little bit more than two billion heartbeats in our lives, and who knows? In the future, we might be able to push it up to three.

Living at Large Scales

In 1999, physicist Geoffrey West and biologists Jim Brown and Brian Enquist found unexpected, interdisciplinary common ground when they set out to find how exactly animals' energy use and needs scale as they get larger or smaller. There'd been a fair amount of research into this already — in the 1930s, biologist Max Kleiber penned what's known today as "Kleiber's Law": metabolic rates scale to the three-quarter power instead of increasing at a one-to-one ratio. This is a bit complicated, but stay with us. Basically, it means that a cat, which is 100 times larger than a mouse, does not use 100 times the energy that a mouse does. Instead, it requires 1003/4 times the energy of a mouse — and that's only about 31.6 times the mouse's requirements.

But what this trio of scientists wanted to discover was far more complex than mere metabolism rates. They wanted to find out how characteristics such as lifespan and pulse rate scaled as well. Those features didn't have the exact same rate as metabolism, but they clearly correlated with each other. Lifespan tended to scale to the power of one-quarter, and heart rate at the power of negative one-quarter. In other words, there's a mathematical equation that lets you predict exactly how long an animal will live and how fast its heart will beat, based on its size.

This article first appeared on Curiosity.com.

.jpg.rend.hgtvcom.476.476.suffix/1571945046392.jpeg)