Getty Images

3 Animals That Mourn Their Dead

Grieving customs aren't just limited to humans.

It's hard to see the world through another animal's eyes. That's especially true when it comes to animal grief — we humans don't always know it when we see it. Human grieving customs are distinctive and unambiguous, but what does it look like for an animal to grieve?

Getty Images

How Do Animals Grieve?

The answer depends on the animal, but Barbara King, an anthropologist and science writer who studies and writes about the topic, says that animal grief is defined by "some visible response to death that goes beyond curiosity or exploration to include altered daily routines plus signs of emotional distress."

Scientists thought for a long time that only humans and our smartest evolutionary cousins were capable of grief and mourning, but new research into animal behavior is showing us that displays of grief can be found throughout the animal kingdom. In the past few years, researchers have developed a new interdisciplinary field, called "comparative thanatology" — the scientific study of death and dying in other species — that should bring deeper insights into how animals respond to death. Find out below how three well-known animals handle death in their communities.

Elephants

Scientists have long known about elephants' response to death. When a living elephant comes in contact with a dead elephant, it usually falls silent and often spends several minutes investigating the body with its trunk and feet. In her 2013 book on animal mourning, King describes several elephants' responses to the death of Eleanor, the elderly matriarch of an elephant family living on Samburu National Reserve in Kenya.

In her final hours, Eleanor had grown weak and collapsed. Within a few minutes Grace, the matriarch from another family, used her trunk to get the dying elephant back on her feet, but Eleanor was very near death and collapsed again. King writes that Grace grew "visibly distressed" by Eleanor's condition. She stayed with Eleanor, vocalizing and pushing at her body. After Eleanor died, elephants from five different families visited her body. The survivors hovered over it, rocked it back and forth, and pulled on it with their trunks. While some of Eleanor's visitors were merely curious, King writes that those behaviors by Grace and other elephants "clearly involved grief."

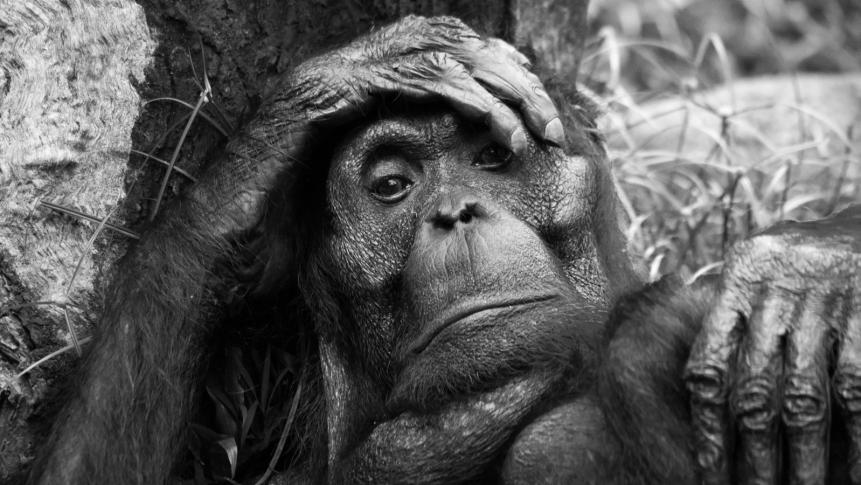

Gorillas

The scientific literature contains several accounts of mourning by other non-human primates (our closest evolutionary relatives). In 2019 Researchers in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo described three instances of gorillas mourning their dead in an article in PeerJ. On one occasion, researchers watched as two mountain gorillas — a 35-year-old dominant adult male and a 38-year-old dominant adult female — died of natural causes within a few hours of each other. Surviving gorillas they had social bonds with spent a lot of time with the dead. A juvenile spent two days with one of the bodies and slept next to it in a nest. One of the female's sons groomed his mother's corpse and even tried to suckle, despite having been weaned.

On another occasion, researchers watched as a group of Grauer's gorillas came across one of their dead in Kahuzi-Biega National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo. Much like the surviving mountain gorillas, the Grauer's gorillas that found the body, sat near, and looked at the deceased while occasionally sniffing and poking the body. Some mourners also groomed and licked it.

Songbirds

Recent research suggests that songbirds use death as an opportunity to grow closer. In an experiment reported in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, researchers from Oxford University showed that the number and intensity of social relationships strengthened among "surviving" birds after researchers temporarily removed one wild great tit from a group of their flockmates. The researchers followed a flock of 500 birds for the winter and occasionally removed randomly selected birds to see how the others would react.

"We found that individual birds adapt to losing a flockmate by increasing not only the number and tightness of their social relationships to others, but also their overall connectedness within the social network of remaining individuals," according to lead author Josh Firth, who is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Oxford.

The results bring to mind the sentiment Minerva McGonagall conveyed in Harry Potter when reassuring two lovers that after one character's death, he "would have been happier than anybody to think that there was a little more love in the world."

This article first appeared on Curiosity.com.