Tetra Images

Electric vs. Hydrogen: The Pros and Cons of Greener Transportation

Transport is one industry that needs to rapidly cut carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions to tackle climate change.

Domestic car use alone accounts for roughly one-tenth of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. So switching to zero-emission vehicles is the only option, but electric cars are no longer the obvious choice and hydrogen vehicles could speed up the transition.

Building cars for lower carbon emissions has become a more difficult global issue for manufacturers to negotiate. Demand for new vehicles fell abruptly as people travelled and commuted less during the coronavirus pandemic. Then a global computer chip shortage shut down car plants, wiping out profits that could have been reinvested in change.

On top of that, scarcity and rising prices for raw materials, including cobalt and nickel for electric vehicle (EV) batteries, means that increasing production and meeting emissions targets will be more difficult. But it could hasten the adoption of hydrogen cars as governments favor hydrogen power alongside renewable energy to replace fossil fuels

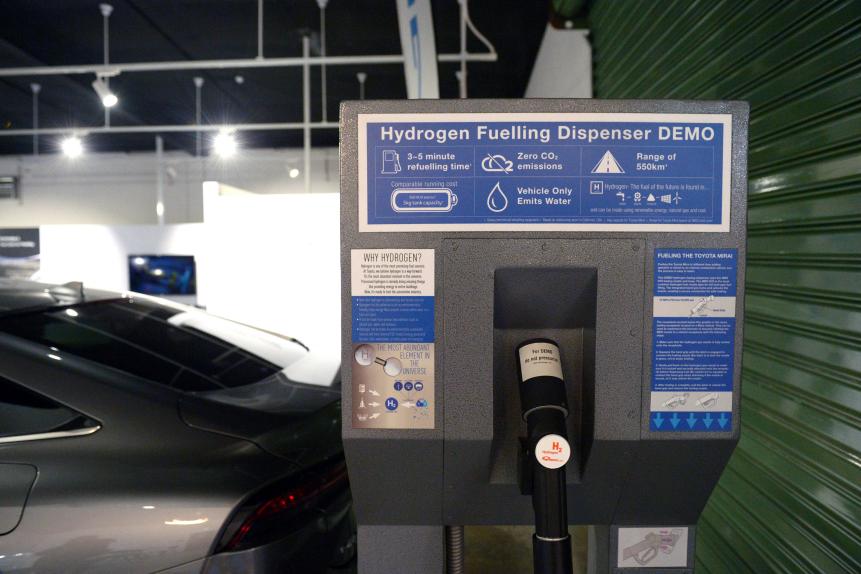

Bloomberg

A hydrogen fueling dispenser at Toyota Motor Corp.'s Hydrogen Center in Altona, Victoria, Australia, on Monday, March 29, 2021. Toyota unveiled its first hydrogen production and re-fueling facility in Victoria.

The EV already has a big head start. Most car manufacturers make battery-powered or hybrid electric vehicles. Electric cars plug directly into national power grids, create zero emissions when driven and have an expanding infrastructure of charging points. But, apart from the more expensive models, they don't have the longer range of hydrogen fuel cell cars and take a long time to recharge compared to a five-minute gas refill.

Prices for producing renewable or 'green hydrogen' are expected to be four times cheaper by 2030, and virtually unlimited supplies for the gas make it an attractive alternative. Fuel cells and hydrogen combustion engines are seen as the solution for zero carbon transport where batteries are either too heavy or impractical to use in shipping, air travel, rail, buses, trucks and construction vehicles.

Governments are backing green hydrogen alongside wind and solar power to do the heavy lifting in public transport, energy storage, freight and areas like steel production. That means switching hydrogen production plants from reforming natural gas to water electrolysis – water split into oxygen and hydrogen using electric current and catalysts.

Innovation in the hydrogen industry is gathering pace rapidly. Catalysts for low voltage electrolysis of hydrogen from seawater and wastewater, using solar and wind power, will vastly reduce the price of industrial production. A team of US researchers has also created a process to produce hydrogen from methane found in natural gas, that releases zero CO2 and creates carbon solids used in manufacturing.

Critics of hydrogen cars often point to the lack of pump infrastructure available – there are only around 50 public refuelling stations in the US – but existing gas stations and pipelines could be adapted and used. Countries like Japan are investing much more in hydrogen cars, providing subsidies to take domestic car travel towards zero-emission.

Richard Newstead

But with all of the surplus offered by the hydrogen economy there is a scarcity issue that cannot be avoided – platinum used in fuel cells is in short supply. Durable new catalysts that use a fraction of the platinum in current fuel cells, plus metal-free polymer catalysts can solve that problem and allow the mass roll-out of hydrogen vehicles.

Yet despite an international push to kick start the hydrogen economy, and enthusiastic reports on the performance and reliability of fuel cell cars, auto makers themselves appear divided. Volkswagen and some other European manufacturers are ditching plans for fuel cell cars at the same time that Jaguar Land Rover is refreshing its line-up with hydrogen, joining eastern brands Toyota and Hyundai pushing the technology forward.

Critics of the hydrogen vehicle strategy also point to the fact that hydrogen combustion engines can produce the greenhouse gas NOx if not properly regulated. Plus the effects of hydrogen leaks can deplete the ozone layer, so designing the infrastructure with safety first makes sense

Hydrogen cars may be five to ten years behind EVs in terms of acceptance, but hydrogen and electric vehicles are likely to happen in parallel as governments tackle transport emissions. Accelerated research is bringing technologies that make the car a viable proposition and falling prices mean policy makers find hydrogen economy solutions increasingly attractive.