HeliRy

Catch-22: How the Clean Energy Industry is Perpetuating Deep-Sea Mining

Stuck in a gridlock, critics of deep-sea mining fear for its negative impact on the environment, yet one of the largest customers of deep-sea minerals is the clean-energy industry.

The increasing popularity of clean energy technology is exciting. As electric cars grow in popularity, so does the possibility of reducing our carbon footprint, shrinking the demand for fossil fuels, and cutting down on toxic emissions.

Clean energy technologies like the lithium-ion batteries used in electric cars (like Tesla), solar panels, and wind turbines have created a rapidly growing market for polymetallic nodules, metals, and minerals that lie in potato-sized chunks on the deep seafloor.

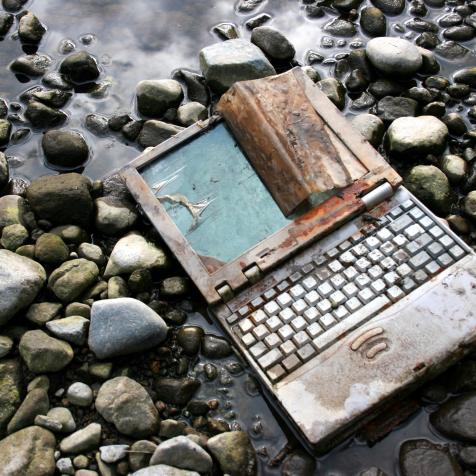

Polymetallic nodules form on or just below the abyssal plains of the deep ocean floor. These valuable lumps are formed when something (like a shark tooth) falls to the bottom of the ocean, and minerals build up on its surface over millions of years. Polymetallic nodules mainly contain manganese and iron, onto which metals like nickel, cobalt, copper, titanium, and rare earth elements absorb.

MonumentalDoom

Polymetallic nodule from 16,000 feet deep in the Pacific Ocean.

While these nodules speckle the deep ocean all around the world, they are most plentiful in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a 1.7-million-square-mile stretch in the international waters of the Pacific Ocean.

Polymetallic nodules are in such high demand because they contain four essential battery metals: cobalt, nickel, copper, and magnesium in a single ore.

As the clean-energy industry continues to grow, demand for these metals is skyrocketing.

Unlike land ores, polymetallic nodules don’t contain unusable heavy elements. Producing metals from deep-sea nodules generates 70% less carbon dioxide emissions and 99% less solid waste than mining on land.

Experts estimate that polymetallic nodules hold six times as much cobalt and triple as much nickel as there is on land, and at a much higher grade. Mining these nodules from the ocean floor could theoretically be the cleanest path toward electric vehicles.

the_burtons

The race for electric vehicle (EV) batteries is driving the market for Polymetallic nodules.

But critics say harvesting these minerals from the deep sea could cause irreversible damage to one of the last natural ecosystems in the world. Mining machines, which can be larger than bulldozers, will likely spread sediment, smothering nearby life — burying an essential part of the food web, and even accelerating climate change by kicking up long-undisturbed carbon stores in the ocean floor.

Dive Amon, an executive at the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative, said, “Going into a new habitat to potentially destroy it and reap the metals that will be used to move us away from climate change … well, we’re destroying one habitat to save another and not fixing the problem.”

Mining machines are also very loud. Noise travels further in water than on land, and can interfere with marine mammals like dolphins and whales’ ability to communicate, feed, migrate, and mate.

A couple of car manufacturers and smartphone companies are also pushing for caution: Google, Volvo, BMW, and Samsung have encouraged a moratorium on deep-sea mining, saying they will not source minerals mined from the ocean for now.

Scientists are alarmed by the lack of data available about the possible consequences of deep-sea mining. A group of more than 500 scientists and marine policy experts signed a statement arguing that deep-sea mining could result in “the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning that would be irreversible on multi-generational timescales.”

Current practices of mining on land aren’t perfect, either. Many Chinese companies have already bought up the lion’s share of the world’s cobalt, a key component used in rechargeable batteries, which could leave the US and EU countries unable to hit their deadlines for the switch to electric vehicles.

Currently, cobalt mainly comes from mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where investigators have found child workers, and inhuman —even deadly, labor conditions.

Carolyn Cole

Gerard Barron in front of The Metals Company's ship in San Diego, CA.

“Transitioning away from fossil fuels is essential,” said the CEO of The Metals Company, Gerard Barron. Achieving a planet run on clean energy will require a lot more mining, so the world will have to weigh the impacts of increased metal production from either the land or sea. “We’re really heading to a period of tradeoffs because there isn’t a perfect solution. I think that’s the key thing.”

As the ocean-mining industry spurs into action, the eyes of the world are watching to see what the next move is for green energy.