AGF

Women May Have Been Powerful Rulers of the Ancient World

A discovery in Spain has experts wondering whether women were once powerful rulers in ancient Europe.

A treasure trove of jewelry, including a silver diadem – a jeweled headband worn as a symbol of sovereignty – was uncovered by archaeologists at La Almoloya, a site in Murcia, southeastern Spain that is the cradle of the El Argar civilization, which lived in the region during the Bronze Age.

La Almoloya was a primary center of politics and wealth in the El Argar territory, and although the discovery was made in 2014, experts are now taking a closer look at the sociological and political context of the unearthed treasure.

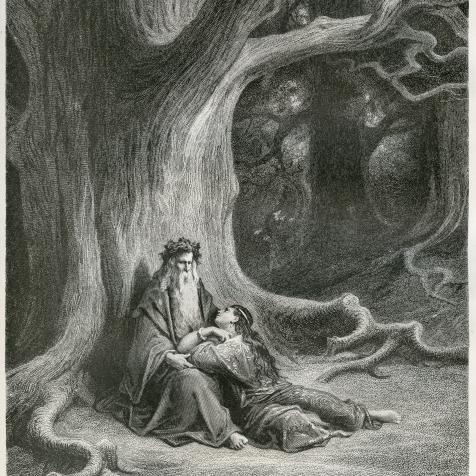

The remains of a woman, along with a man who may have been her consort, were discovered in the forested hills of the area. Radiocarbon dating suggests the burial happened around 1700 BC, and researchers believe that the woman had a prominent role in her community.

The pair were found with 30 objects containing precious metals and semi-precious stones, including the silver diadem with a disc-shaped appendix that would have been worn pointing downwards, which encircled the skull of the woman.

Experts believe that the man in the grave was probably a warrior; wear and tear on his bones indicate he spent a lot of time on horseback, and his skull had deep scars from a facial injury, while gold plugs through his earlobes indicated he was someone of distinction.

The woman, dubbed the “Princess of La Almoloya”, was buried a short time after the man, with particular grandiosity: bracelets, earlobe plugs, rings, and spirals of silver wires, to name a few. The grave goods of the woman were worth tens of thousands of dollars in today’s money.

“We have two ways of interpreting this,” says archaeologist Roberto Risch of the Autonomous University of Barcelona. “Either you say, it's just the wife of the king; or you say, no, she’s a political personality by herself.”

Risch is a co-author of a study that was recently published about the important findings, that noted the building under which the grave was found was of equal importance – possibly being one of the first Bronze Age palaces identified in Western Europe.

The original excavation was conducted by researchers at the University of Barcelona’s Department of Prehistory. Archaeologists also found an urban plan made up of fully equipped buildings, dozens of tombs, and evidence that there were several residential complexes, with eight to 10 rooms in each building. It was also the first time a building specifically dedicated to governing purposes had been discovered in Western Europe– a wide hall was excavated, with high ceilings, a podium, and a capacity for 64 people to sit on benches that lined the walls.

The discovery at La Almoloya shed new light on the politics and gender relations in one of the first urban societies of the West. Previous findings have revealed that women were considered adults at a much younger age than boys were. Excavated grave goods have highlighted that girls as young as six were buried with knives and tools, but boys would be in their teens by the time they would be buried alongside such ornaments.

Additionally, the graves of some women from El Argar were reopened generations later to inter other men and women, an unusual practice that experts believe would have been a very high honor.

“What exactly their political power was, we don't know,” Risch adds. “But this burial at La Almoloya questions the role of women in [Bronze Age] politics… it questions a lot of conventional wisdom.”.