Emiliano Ruprah

Surprises from Emiliano Ruprah’s Adventures in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley

Arbore, Dassenetch, Karo, Konso... These are some of the most fascinating tribes from the Omo Valley, Ethiopia.

As we finished filming UNEXPLAINED AND UNEXPLORED, I decided to head south to the Omo River Valley, to meet some of Ethiopia’s most fascinating tribes. The Lower Omo Valley is a melting pot of cultures and communities and represents some of the greatest genetic variances on the African continent. Many describe the Omo as being the birthplace of mankind. Zab, my guide offers to introduce me to local tribes, telling me, ”if you are kind and likable, they will invite you to their villages and teach you about their way of life.” Our first stop is Kayafar Market.

The Kayafar Market

The Kayafar market is where eleven tribes sell and trade goods. It has a cattle market, where a rainbow coalition of men from various tribes don the traditional colors of their people and trade cattle to the highest bidder. Some animals will go on to plow the fields, others will provide milk and butter, and the unlucky ones will be sacrificed for their meat. This is where Ethiopia’s best meat comes from, much of it consumed raw in delicacies like kitfo (raw beef) or Shania (raw cow hump).

Emiliano Ruprah

During this visit, Zab’s friend offers some insight into an ancient practice known as Mingei. Mingei are babies born with deficiencies, or more commonly, out of wedlock. They are sacrificed in sacred places called kopa by having their arms and legs wrapped in leather and by having their mouth and other orifices blocked with earth, cow dung, and butter. The Ethiopian government works with several NGOs to identify the locations of kopa and save babies before it’s too late. As we leave the market, Zab explained that his friend had been saved when an NGO had first begun these efforts in Ethiopia.

Other parts of the market sell fresh produce and medicinal herbs, honey, and two types of butter — one used for cooking and the other is mixed with red clay and worn on hair by women from several tribes, like the Hamar, who are known for their ruby hair locks. This market is hundreds of years old and fulfills a very practical function: to trade goods, build social cohesion among tribes, and for people — particularly women — to socialize. According to Zab, “the market is a weekly means of reuniting with family members and friends from far and wide — it really belongs to the women.” As I looked around the dazzling array of goods and people I began to notice how elaborate greetings among women were. Women from all tribes had their own ways of saying "hello" — complicated handshakes followed by touching shoulders or snapping fingers.

Karo Village

Situated close to the Kenyan border on a high cliff overlooking the Omo River, the Karo Village was made up of dozens of circular huts constructed from sticks with pitched grass roofs sprawled across verdant flats. Painted in glimmering white patterns, men sat with Ak47’s under the shade of an Acacia tree. Next to them, children played a ball game raising clouds of dust past a group of women, who lay on skin hides treating each other’s hair with red clay.

Emiliano Ruprah

Zab introduced me to Lale Biwa, a young man who would show me around the village. We drank coffee inside his hut and shared tobacco snuff made from ground tobacco mixed with Earth. We went down to the river, where men were fishing with nets and walked past fields of maize. Lale Biwa says, “Everything is good. If we can protect ourselves from enemies we are good. But we have guns. So it's okay.” After a few more drinks, he invited me back to watch his oldest brother’s bull jumping initiation rite — a celebration of manhood. Though I could not attend, they asked if they could “paint me like a Karo”— an honor I gladly accepted.

While Lale Biwa and his uncle painted me with white clay, they explained that a massive hydro-electric dam had been built on the Omo river in order to support vast commercial plantations that are forcing the tribes from their land. This has caused periodic conflicts between tribes as they compete for natural resources. As the outside world is quickly encroaches, competition for scarce resources has intensified and firearms has made inter-ethnic fighting more dangerous.

Arbore Village

As soon as we reached an Arbore village we were surrounded. Young and old alike came running from their huts, the elders supported by walking sticks or dragged by their more energetic counterparts, rushed to greet us. I managed to communicate with the elders and struck a deal: I would donate a fair sum for the village as a whole. All I wanted was to spend the day with them and to learn about their lives.

Emiliano Ruprah

Over coffee served in gigantic gourds in his hut, Goranke, almost 90 years old, told me about the way the Arbore world was shifting. As the government built roads to facilitate commercial plantations, tourists had gained unprecedented access to Arbore villages. The interaction was always the same: pose for a selfie, an Instagram video, or a picture and you’ll be paid individually. This kind of transactional relationship with outsiders had birthed the scramble I witnessed earlier. In fact, I was the first person to visit their village to actually sit and share coffee with his family, he told me.

In honor of our friendship, I would leave the village bearing the imprint of the Arbore: intricate patterns are drawn on my face by young, unmarried men. As a 15-year-old carefully transformed my countenance into a pointillist masterpiece, Goranke joked that I was too old to be unmarried and should consider settling with the Arbore, though I would have to come back with enough cattle to support a family. I left their village wearing face paint made from the various clays of their fertile lands.

The Konso

Three hours into the mountainside, the Konso live in stone-walled terraces and fortified settlements in the highlands. Zab describes them as “the hardest working people in Ethiopia.”

Emiliano Ruprah

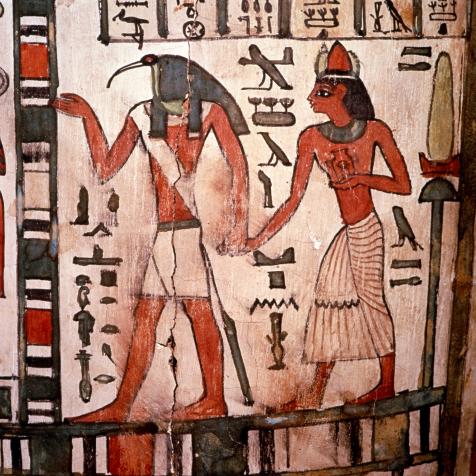

Belachew Beyene, a student from one of the oldest Konso villages met us at the entrance of his town. His ancient village is a UNESCO world heritage site. The town was surrounded by defensive walls and pathways that spiraled past ancient huts built from wood and stone. Each family had an entrance and huts on two levels: the high huts for the family, and the low huts, separated by a terrace, for cows and chickens. The town had a series of shared grounds for rituals and prayer. These shared sacred spaces were open to Christians and animists alike — the two major religions of the Konso. At the center of it, all lay towering wooden poles stacked together. The poles were tied into a vertical bundle with rope and decorated with monkey skulls. Each pole was placed every 18 years. It’s a way for the town to celebrate its age. I calculated 45 poles, making this village 810 years old.

The Konso graveyards were masterpieces of craftsmanship as well. Next to important graves, wooden anthropomorphic statues (waka), carved out of hardwood and mimicking the deceased, are erected as grave markers. But the ones I photographed were all for show. Belachew told me all the real ones had been stolen, most likely by tourists. This is when I realized that this village was a museum. Some people lived there, but many of the customs were kept up as part of a living exhibit for tourists. Tourism has irreversibly transformed their way of life — for better or for worse.

The Dassenetch

The Dassenetch live across the river from the Arbore, but there are no roads that lead directly to their homes, and you need to take a dugout canoe across the Omo river to meet them.

Emiliano Ruprah

Over coffee with Esho Tafes, a Dassenetch representative, we swapped stories. His family and friends taught me to spray coffee into clouds of mist over their laughing children as a blessing. “We live in the umbilical cord of god,” Esho’s brother, a young father, told me as he wiped the coffee mist from his child’s face. “It connects us to the sky and to the great mother. This is why we bless our children with her gifts”. Eventually, the conversation turned to tourism. Esho echoed the sentiment of the Arbore elder I had met a few days prior. “Not many come to visit, we are far. But when they come, they come to take pictures. They see us as wild men, savages. But it is a source of income for our village. Never has a 'white man' sat down and shared stories, and showed us their life.” I told them that I’m half Sicilian and half Indian — not white by American standards. I ask if they'd be interested in visiting me. Esho’s father, one of the village elders, said, “why go? I've already seen you,” but before I left, Esho and I exchanged numbers. He said to me, “maybe I will, maybe I will visit”.